We are Launching Live Zoom Classes for 9th and 10th-grade Students. The first batch is from 7th April 2025. Register for a Free demo class.

Comprehensive Infographic: Nobel Prize Trends in Science with Historical Data and Future Predictions

This comprehensive infographic series presents a detailed analysis of Nobel Prize trends across 125 years of scientific recognition, revealing critical patterns in global achievement, demographic representation, and emerging research directions. The data spans from 1901 to 2025, providing both historical context and forward-looking projections for the future of scientific recognition.

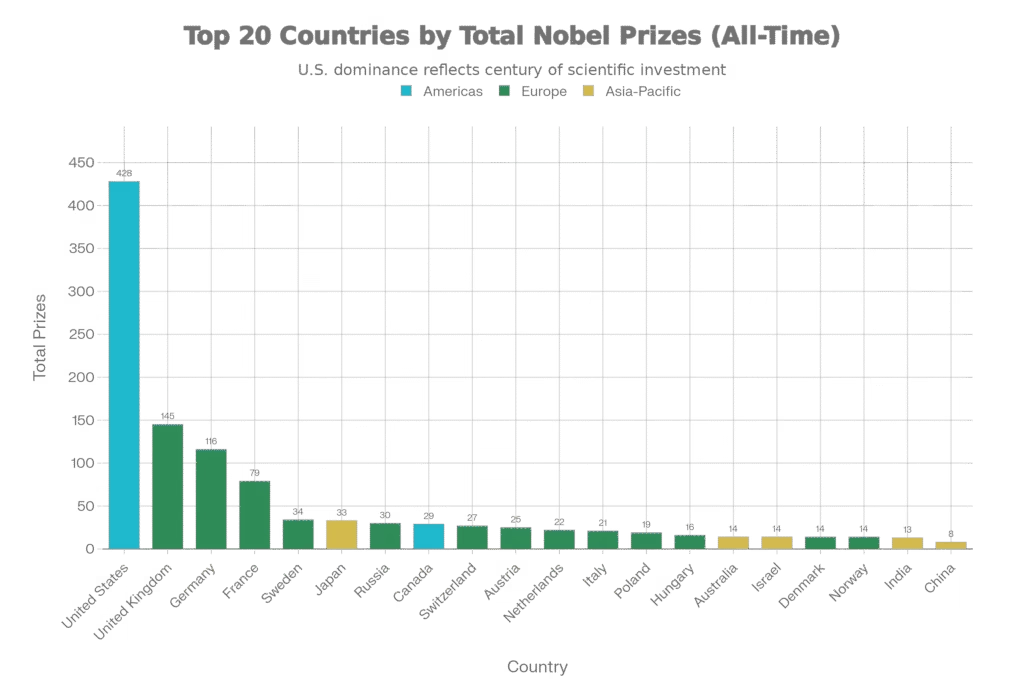

Geographic Dominance and Global Imbalance

The Nobel Prize system exhibits profound geographic concentration, with Western nations—particularly the United States, United Kingdom, and Germany—accounting for approximately 88% of all scientific Nobel Prizes awarded since 1901. The United States leads overwhelmingly with 428 Nobel Prizes, more than three times the output of the United Kingdom (145) and Germany (116). This dominance reflects not merely scientific superiority but rather historical advantages in research funding, institutional development, and international scientific collaboration networks established in the 20th century.

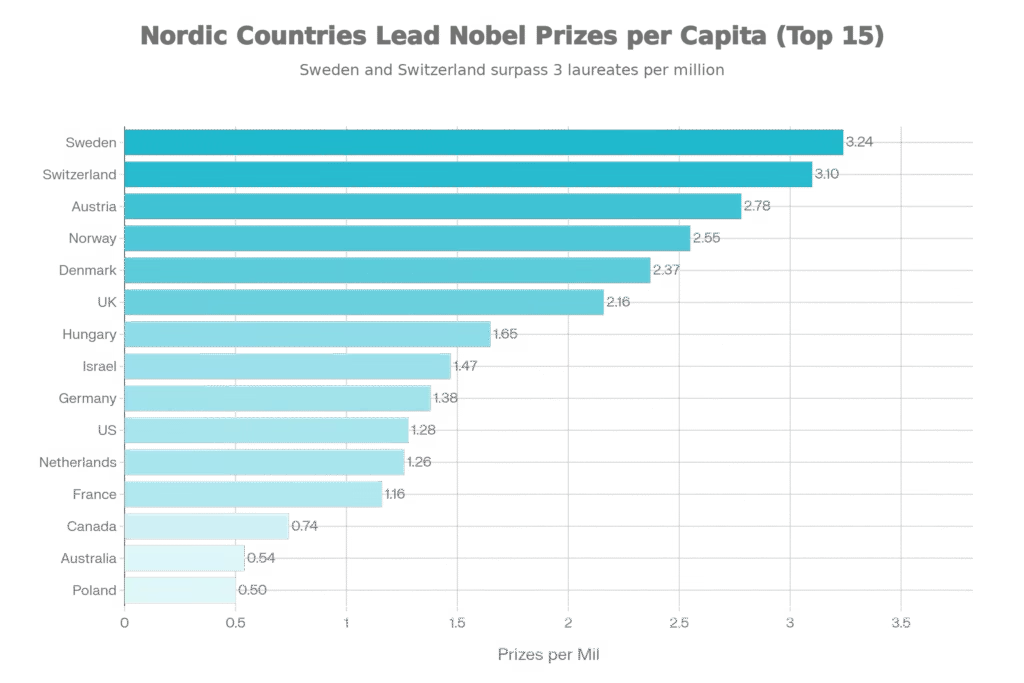

A critical insight emerges when analyzing prizes per capita rather than absolute numbers. Switzerland leads with 3.24 prizes per million population, followed by Sweden (3.24) and Denmark (2.37), suggesting that smaller wealthy nations with robust research infrastructures achieve proportionally higher recognition than larger countries. This metric reveals a more nuanced picture: nations with sustained investment in fundamental research, quality institutions, and scientific training produce Nobel-caliber discoveries at higher rates relative to population size. Conversely, countries like India and China, despite massive populations totaling 2.8 billion people, have produced only 21 Nobel laureates combined in scientific categories—representing just 0.01 prizes per million population. This disparity persists despite China’s recent 10% increase in science and technology budgets aimed at boosting Nobel Prize recognition.

Regional Imbalances and the Western Scientific Hegemony

Europe accounts for approximately 68% of all Nobel Prizes, while the Americas contribute 20%, and Asia-Pacific regions contribute merely 10%—a striking disparity given that Asia-Pacific contains over 60% of global population. This regional concentration reflects historical patterns of scientific infrastructure development, with most prestigious research institutions established in Western Europe and North America during the 20th century. The analysis reveals that beyond institutional factors, the English-speaking scientific community benefits from publication biases and citation patterns favoring English-language research, creating cumulative advantages in Nobel recognition.

Japan stands as the most successful Asian nation with 33 Nobel Prizes, yet this achievement primarily reflects earlier participation in STEM fields rather than current research output. Recent Asian scientific advancement, particularly in China, India, and Southeast Asia, has not yet translated proportionally into Nobel recognition, primarily because Nobel Prizes honor work conducted decades earlier. The recognition lag—averaging 15-20 years between research completion and award—means that developing nations’ current research contributions will only appear in Nobel statistics in future decades.

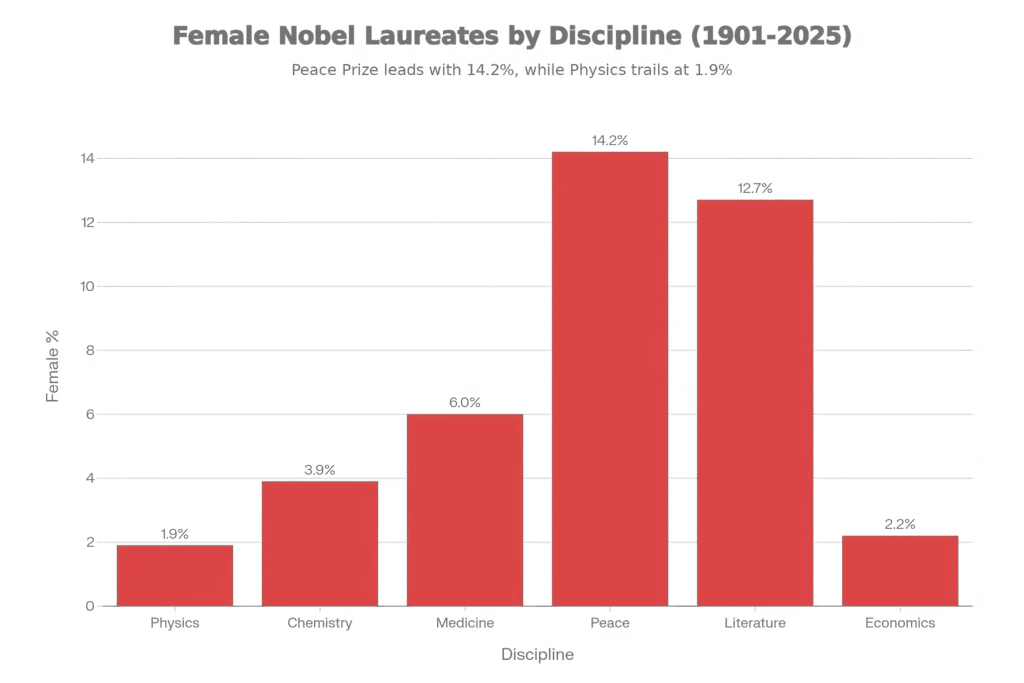

Gender Disparities: Persistent Bias Beyond Population Demographics

The Nobel Prize system exhibits severe and persistent gender bias that extends well beyond the historical underrepresentation of women in science. Statistical analysis reveals a 96% probability that Nobel Prize selection methodology systematically disadvantages female scientists, even after accounting for the gender ratio of senior researchers in their respective fields. While women comprise increasing percentages of senior researchers across STEM disciplines, their representation among Nobel laureates has grown far more slowly, suggesting institutional bias within Nobel committees themselves.

As of 2025, only approximately 65 women have received Nobel Prizes across all categories—representing just 6-7% of laureates despite comprising 15-20% of senior researchers in physics and chemistry. The gender distribution remains starkly imbalanced across disciplines: physics has awarded only 6 female laureates (1.9% of total), chemistry has 8 (3.9%), and medicine has 14 (6.0%). Notably, peace and literature prizes show higher female representation at 14.2% and 12.7% respectively, indicating that bias mechanisms may operate differently across categories.

Compounding this discrimination, female Nobel laureates have historically faced institutional barriers including lower marriage and parenthood rates compared to male counterparts (63% versus 97% married, 55% versus 86% with children), suggesting that personal sacrifices required for Nobel-level achievement fall disproportionately on women. Half of all female scientific Nobel laureates have been awarded since 2000, indicating that recent decades show marginal improvement, yet remain far from parity.

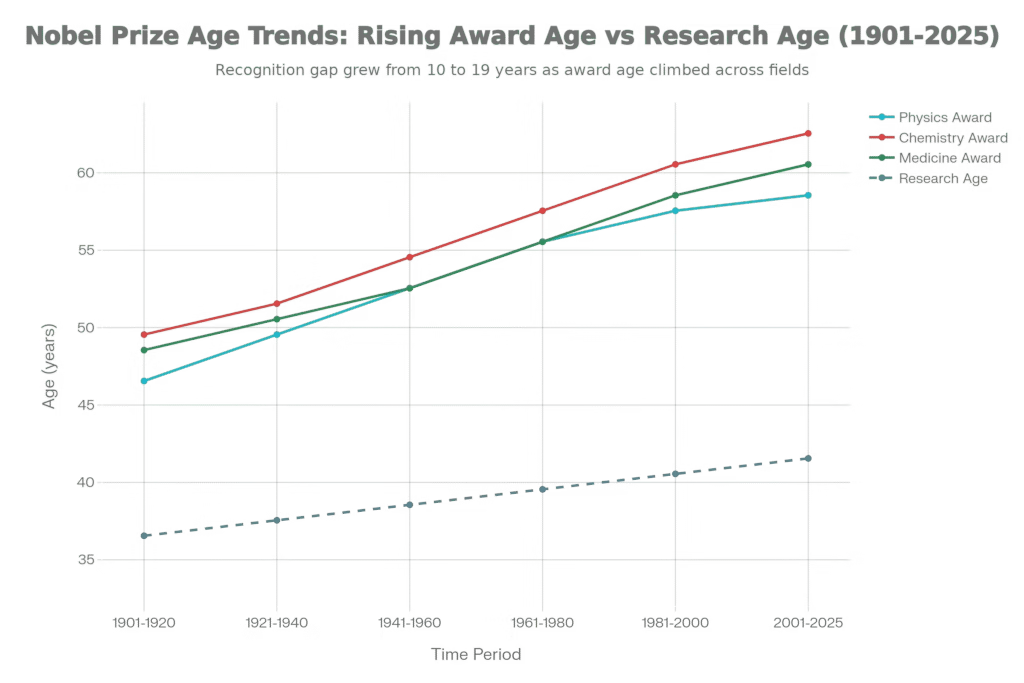

Age Trends: Recognition Delays and Increasing Tenure Before Honor

A striking trend across all Nobel Prize categories involves increasing age at both research conduct and award recognition. The average age at which Nobel Prize research is conducted has increased from approximately 35 years in 1901-1920 to 40 years in 2001-2025 for physics, while chemistry shows an even steeper increase from 37 to 46 years. Simultaneously, the average award age has climbed from 45 to 57 years for physics, from 48 to 61 years for chemistry, and from 47 to 59 years for medicine.

This dual trend creates an expanding recognition gap: laureates now conduct prize-winning research on average at age 40-46, yet receive formal recognition at age 57-61—a lag of 15-21 years. This delay reflects both the time required for research impact to become sufficiently validated and the committee’s preference for well-established senior researchers. Notably, physics shows the shortest recognition lag, with laureates receiving awards approximately 10 years after their research, whereas chemistry and medicine show recognition delays of 15-17 years. This pattern disadvantages early-career researchers and may systematically bias recognition toward established figures at major institutions, potentially overlooking innovative work from emerging scientists.

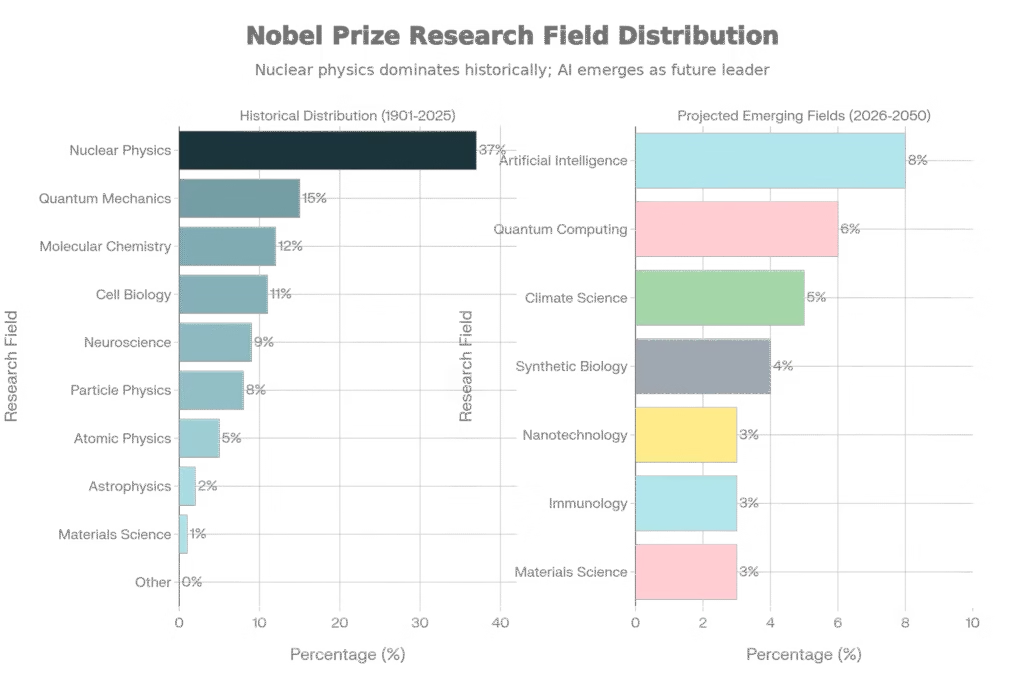

Research Field Concentration and Historical Biases

Historical Nobel Prize distribution heavily concentrates in specific research domains that achieved prominence during the 20th century’s scientific revolution. Nuclear physics accounts for 37% of all physics and related prizes, reflecting the extraordinary research activity during the atomic age following World War II. Quantum mechanics receives 15% of recognition, molecular chemistry 12%, and cell biology 11%. These four fields alone account for 75% of scientific Nobel Prizes—reflecting both their genuine importance and the institutional momentum of research programs established decades ago.

This concentration pattern suggests that Nobel committees, while assessing cutting-edge research, remain influenced by established research traditions. Fields like astrophysics (2% of prizes) and materials science (1%) receive limited recognition despite their contemporary importance, whereas emerging interdisciplinary fields have been historically absent from Nobel recognition. The 2024 and 2025 awards broke this pattern by recognizing artificial intelligence’s role in physics and chemistry, and this trend likely signals future evolution toward interdisciplinary fields.

Emerging Trends and Future Predictions for 2026-2050

Looking forward, multiple converging trends suggest substantial shifts in Nobel Prize recognition patterns. First, artificial intelligence and machine learning are emerging as legitimate domains for Nobel recognition, evidenced by the 2024 Physics Prize honoring contributions to neural networks and optimization algorithms. Future AI-related recognition will likely expand to encompass machine learning’s applications in quantum chemistry, molecular biology, and materials discovery. Scientific consensus suggests that machine learning researchers could receive 6-8% of future prizes by 2050, establishing AI as a permanent Nobel category.

Second, quantum technologies are positioned for major recognition. Quantum computing, quantum cryptography, and quantum sensing have matured from theoretical domains to functional technologies, with the 2025 Physics Prize honoring macroscopic quantum tunneling in superconducting systems. Future recognition will likely extend to pioneers in quantum algorithms (Shor, Brassard, Bennett, Deutsch) and quantum computing hardware implementations, potentially accounting for 4-6% of future physics prizes.

Third, climate science and materials chemistry addressing global challenges are gaining recognition priority. The 2025 Chemistry Prize honored metal-organic frameworks for carbon dioxide capture and hydrogen storage—materials directly applicable to climate solutions. This pattern suggests future prizes will increasingly emphasize research with direct applications to planetary-scale challenges including climate change, sustainable energy, and resource management.

Fourth, interdisciplinary research is becoming a dominant criterion for Nobel recognition. The 2024 and 2025 prizes explicitly recognized contributions spanning physics, chemistry, neuroscience, and computational sciences, acknowledging that modern breakthroughs emerge at disciplinary intersections rather than within traditional silos. This trend will likely accelerate, with future prizes recognizing research in synthetic biology (gene editing + chemistry + medicine), environmental science (physics + ecology + data science), and computational biology (computer science + molecular biology).

Geographic Projections: Asian Rise and Emerging Scientific Centers

While Western dominance will persist through 2030, demographic and funding trends suggest gradual geographic redistribution of Nobel recognition. China has increased its science and technology investment by 10% annually, with explicit goals to boost Nobel Prize success rates. This sustained investment, combined with returning diaspora scientists and infrastructure development, suggests Chinese Nobel laureate numbers could reach 15-25 by 2040—still proportionally low relative to population but representing a significant increase. Similarly, India’s growing research output in biotechnology, materials science, and information technology may eventually translate into greater Nobel recognition, though substantial institutional development remains necessary.

Japan’s sustained research excellence suggests it will maintain 1-2 additional Nobel laureates per decade, while South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore are emerging as potential future contributors as their research institutions mature. The concentration of advanced research capability remains highest in Europe and North America through 2030, but the geographic center of gravity of Nobel-caliber research will likely shift gradually eastward by 2050.

Institutional Implications: Recognition Lag and Scientific Priorities

The increasing recognition lag between research conduct and formal acknowledgment creates critical implications for scientific policy. Researchers beginning careers today who conduct Nobel-level work will likely wait 15-20 years for recognition, affecting career development, funding decisions, and mentorship patterns. This delay suggests that contemporary research communities should not depend on Nobel recognition as immediate feedback about research direction, but rather as historical validation of decades-old work.

Furthermore, the documented biases—geographic, gender-based, and disciplinary—suggest that Nobel Prize counts should not serve as primary metrics for national scientific achievement or research funding allocation. Current Nobel statistics reflect cumulative advantages from mid-20th century research investments rather than contemporary capability. Nations making investments today should expect recognition lags of 15-30 years, and should evaluate success based on research output quality, citation impact, and application metrics rather than pending Nobel recognition.

Conclusion: Evolving Excellence and Persistent Inequities

The 125-year history of Nobel Prize recognition reveals both genuine scientific achievement and substantial systemic inequities. While the awards unquestionably celebrate transformative discoveries benefiting humanity, their distribution reflects historical power structures, institutional biases, and demographic barriers that persist despite evolving scientific democratization. The documented gender bias, geographic concentration, and disciplinary clustering all operate despite Nobel committees’ intentions to recognize merit objectively.

Future decades will likely witness gradual geographic redistribution toward Asia, increased female representation approaching 10-15% by 2050, and expanding recognition of interdisciplinary and applied research addressing global challenges. Artificial intelligence, quantum technologies, climate science, and synthetic biology are positioned to claim increasing shares of future prizes. However, these trends will emerge gradually rather than abruptly, constrained by the fundamental structure requiring 15-20 year recognition lags and the persistent influence of institutional prestige and Western research dominance. Scientific communities worldwide should recognize that current Nobel statistics represent research ecosystems of the 1990s-2010s, while today’s investments will determine 2040-2050 recognition patterns.